Introducing the Straw Man Fallacy – How to Kill the Big Bad Wolf

This article is co-authored by Peter Paskale.

As a presenter, the ability to persuade is imperative, but as an audience member, so is the ability to know when not to let yourself be persuaded. In this article, Peter explains how a rhetorical fallacy can be used to unjustly mislead an audience by subtly slipping in small inaccuracies, and subsequently building an argument based on them.

It’s way easier to blow-down a house of straw. Just ask the big bad wolf.

So it is with arguments. An argument made of straw is easier to demolish than one made of brick. Why therefore, would speakers deliberately choose to build house-of straw arguments?

Because they want to blow them down. All by themselves.

The Straw-Man Fallacy: a well-known communications strategy

A Straw-Man is a false case, that if you can successfully argue is true, will make the case for your larger argument. For example – Britain sends £350 million a week to the EU (widely believed, but untrue), whilst the National Health Service needs more money (true). Therefore leaving the EU will allow an extra £350 million a week to be spent on the NHS. (Sounds logical – but based on a completely false initial premise!).

You won’t be surprised to hear that it’s an absolute favorite among politicians and lobbyists looking to pull a fast-one. Here’s a straw man that I spotted from an American commentator and gun advocate.

During a debate on gun rights, the discussion turned to constitutional rights. Specifically, “Should certain sections of the population be denied the right to own a gun?”

The gun advocate cited blind people, and made a strong case that it constituted unfair discrimination to deny them the same Second Amendment rights as the rest of us. In other words, blind people should have guns too!

This was a Straw-Man! America’s 1968 Gun Control Act makes no mention of blind people. According to that act, the blind already have precisely the same gun rights as everyone else.

Why would the gun advocate deliberately argue a case that didn’t exist?

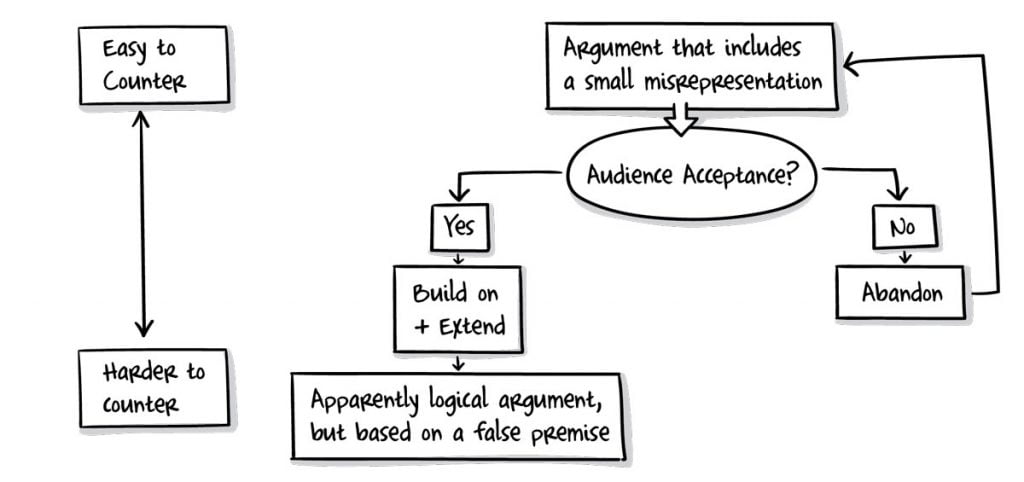

It was all rather odd and circular, but done for a reason, because creating a Straw Man Fallacy is only stage one of a larger plan:

Step One: The straw-man

Let’s say that blind people represent Group A. The speaker set-up a Straw-Man that led us, the audience, to inaccurately believe that blind people were unfairly discriminated against under the Gun Control Act.

Step Two: The demolition

He then built a powerful case for why that was wrong. He had created a compelling argument against an illusionary target of his own creation.

Step Three: The extension

By showing that Group A are being unfairly discriminated against, then we as an audience might become pre-inclined to believe that maybe groups B & C are also being prejudiced against.

Step Four: The precedent

While Group A is the illusory Straw-Man, groups B & C will be real. A successful Straw-Man will have created a precedent. Given A, it can now be argued that groups B & C, (who are genuinely banned under the Gun Control Act), should also be able to carry fire-arms.

It’s all extremely Machiavellian but whenever you detect a speaker creating a Straw-Man then it’s only step one of a wider plan. When the strategy is wielded in the hands of a political pro, you may even see the deployment of a little escalating line of them, all becoming progressively bigger!

In this form, the speaker will start with the tiniest of Straw Men (more of a Corn Dolly in fact), that features just the tiniest misrepresentation. If that one is swallowed undetected, they will move onto a slightly larger one, followed by the actual Straw Man itself.

Think of it as being like tenderizing the audience to check just how much can be slipped past them before you hit the big lie.

It’s been said that all is fair in love, war, and debate, and indeed, by the accepted rules if you slip a fallacy past your opponent undetected and then use that to build your argument, then all power to you. However, as with all deliberate use of fallacy when arguing, many of us instinctively feel like someone is committing a foul. And that’s precisely why it’s a good idea to know about this tactic, even if you yourself would never use it.

To understand it is to be able to rebut it.

If something doesn’t sound quite right, then it probably isn’t

Few debaters want to be caught in a deliberate lie. After all, that demolishes their credibility. So if you ever suspect that someone is building themselves a house of straw, be brave. Politely challenge them in the moment. Rather than being unmasked, all but the most mendacious of debaters will duck down behind the ‘honest mistake’ or the ‘you misunderstood me’ excuse rather than dig-in deeper.

There are times in every presenters’ life when we need to be the Big Bad Wolf and give that house of straw a darned good blow. If allowed to stand, then the fallacious argument that it’s building up to will rapidly be converted to bricks.

Bricks are way harder to demolish.

Jim Harvey

30th July 2016 at 7:58 pm

Great post Peter, thank you. So to destroy a straw man fallacy you’re suggesting that we have to destroy the first case, in this example, that blind people are not excluded from carrying arms under the US constitution. So we say ‘That’s ridiculous, there’s no case there, try harder…’

Peter Paskale

2nd August 2016 at 3:01 pm

Absolutely Jim. That, in a nutshell, is the best way to deal with them. For example – in the US election right now there is intense debate about immigration across the Mexican border. This case has been built and built until it’s become a discussion about a wall and exactly how high that wall should be. — The initial straw man though was the argument that immigration is an issue.Latest data shows illegal immigration across the border to have been falling for the past few years, and to now be extremely low. Had that been successfully pointed out at the beginning, and that first little corn dolly neutralized, we might now be hearing a very different discussion.